1912

IT HAPPENED IN…1912

New Mexico and Arizona were admitted to the

Union.

The presidential election pitted former President

Theodore Roosevelt against incumbent President William Howard Taft

and Woodrow Wilson, Governor of New Jersey.

Wilson won in a landslide.

The British ocean liner

Titanic sank on its

maiden voyage, killing about 1,500 persons.

Newly introduced products included Life Savers

candy, and shopping bags.

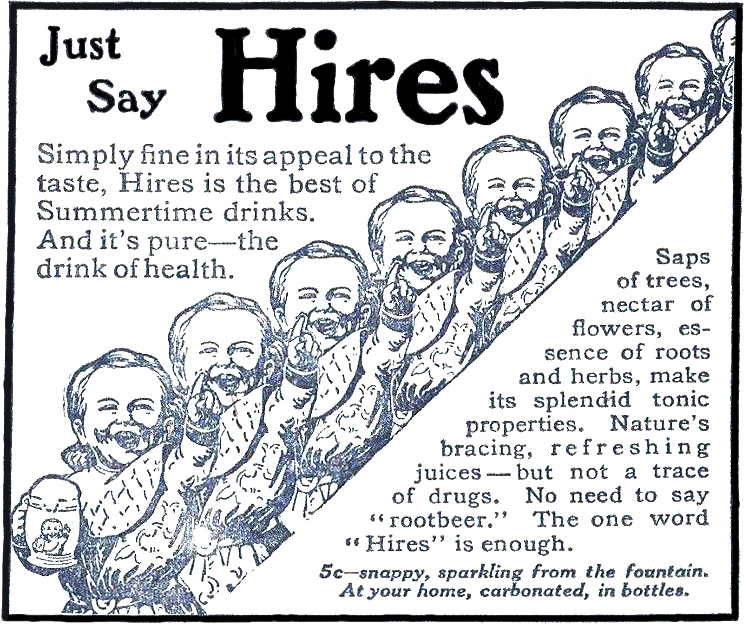

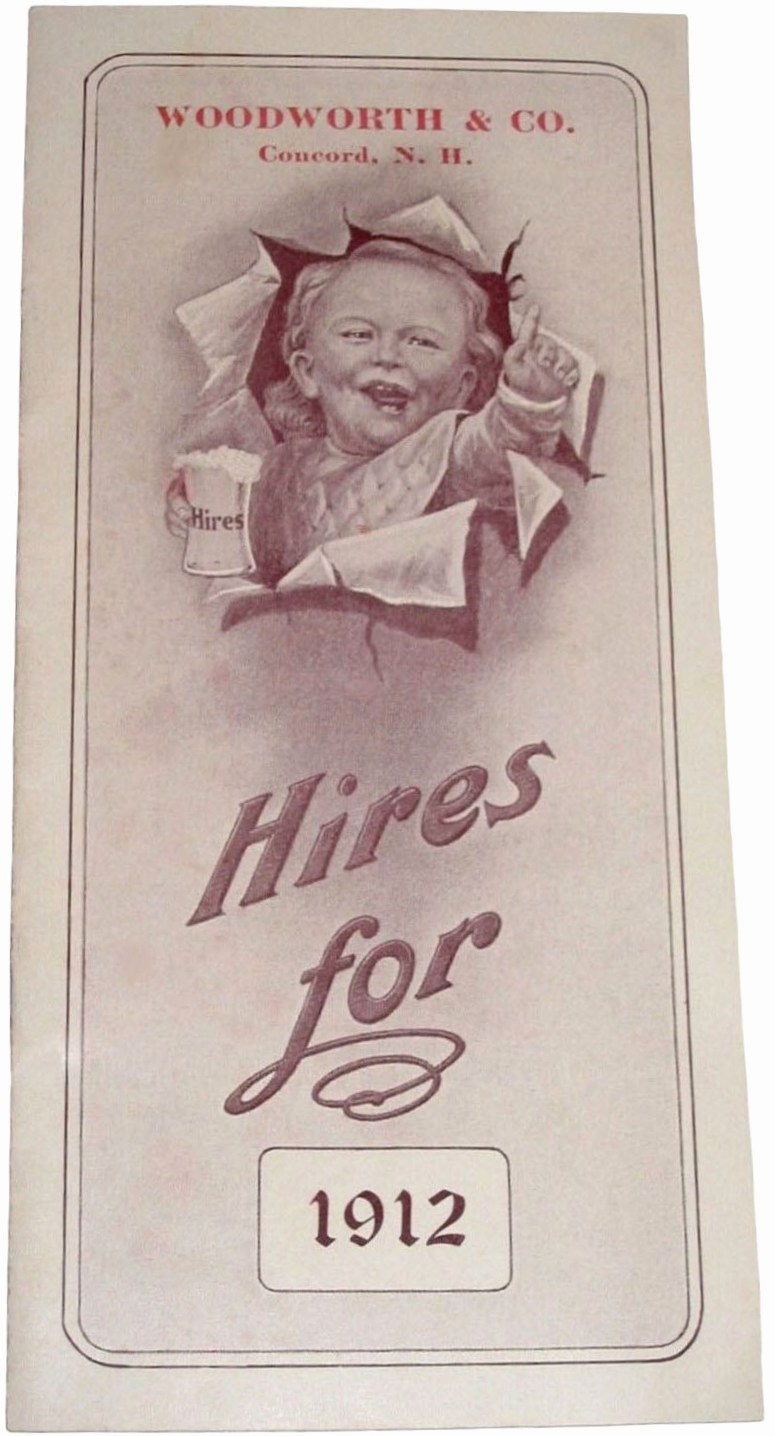

Early in 1912 Hires printed cardboard booklets for use by their wholesale distributors that supplied Hires' products to soda fountains. The cover art from a similar 1910 brochure (see Figure 1910-01) was updated, and eight pages inserted listing a wide variety of available products. The front cover of the pictured example was overprinted by Woodworth and Company, a major grocery supplier located in Concord, New Hampshire, and in turn distributed to Woodworth & Co''s retail customers.

(Figure 1912-00, Hires for

1912 booklet, 6.75” x 3.0”)

The inside front cover of the 1912 booklet included this information about Hires' "Nufrute" brand products:

For a generation, the "SMITH & PAINTER" brand of Concentrated Fruit Juices, Crushed Fruits, Natural Fruit Juices and Fruit Syrups has been the acknowledged standard of quality on the market, without any exception. Our Nufrute Products are the celebrated "SMITH & PAINTER" brand, made by their process wholly and directly from the fruit, exactly as they have been made for the past forty-odd years.

"SMITH & PAINTER'S" Natural Fruit Juices have never contained sodium benzoate nor any other preservative. They are the same today as when first introduced; no change in method of preparation made necessary by food laws.

Our "NUFRUTE SPECIALS" are strictly of our own creation and cannot be duplicated elsewhere. If you want to serve a "specialty," ask for "NUFRUTE SPECIALS."

Our reputation for quality and guarantee for purity, which made "Hires" famous the world over, protects you in your purchase of all our "NUFRUTE PRODUCTS."

A wide variety of "Fountain Syrups - Concentrated - Made from the juice of fresh, ripe fruit and the finest cane sugar" were available, most for $2.00 per gallon. "Crushed Fruits - Put up in half-gallon jars, 6 to the crate" were also offered.

Other advertisements in the 1912 booklet included these offerings:

Hires Syrup Jars - Made of fine white porcelain, gracefully shaped, an attraction for any counter. The pump is silvered, jeweler's finish. Holds 1 Gallon Syrup and measures automatically the proper amount of syrup for a perfect drink. Price $10 Net.

Hires Dispensing Glasses - Hold 10 oz. Have oz. mark to measure the Syrup. The ideal size for general fountain use. 60¢ doz.

The Munimaker - A complete Soda-Fountain and Syrup-Dispenser combined. Made of white marble Pipes silver-plated jeweler's finish. Draws coarse stream, fine stream and Hires, perfectly blended. Price, $150.00 only. Sold on easy monthly payments.

This paper invoice dated April 16, 1912 reveals bottler’s syrup was $1.50 per

gallon, with a 3% discount if paid with 30 days.

Form 336 continued to indicate The Charles E. Hires Company was

established in 1870.

(Figure 1912-01, Form 336

invoice, April 15, 1912, 8.25” x 6.75”)

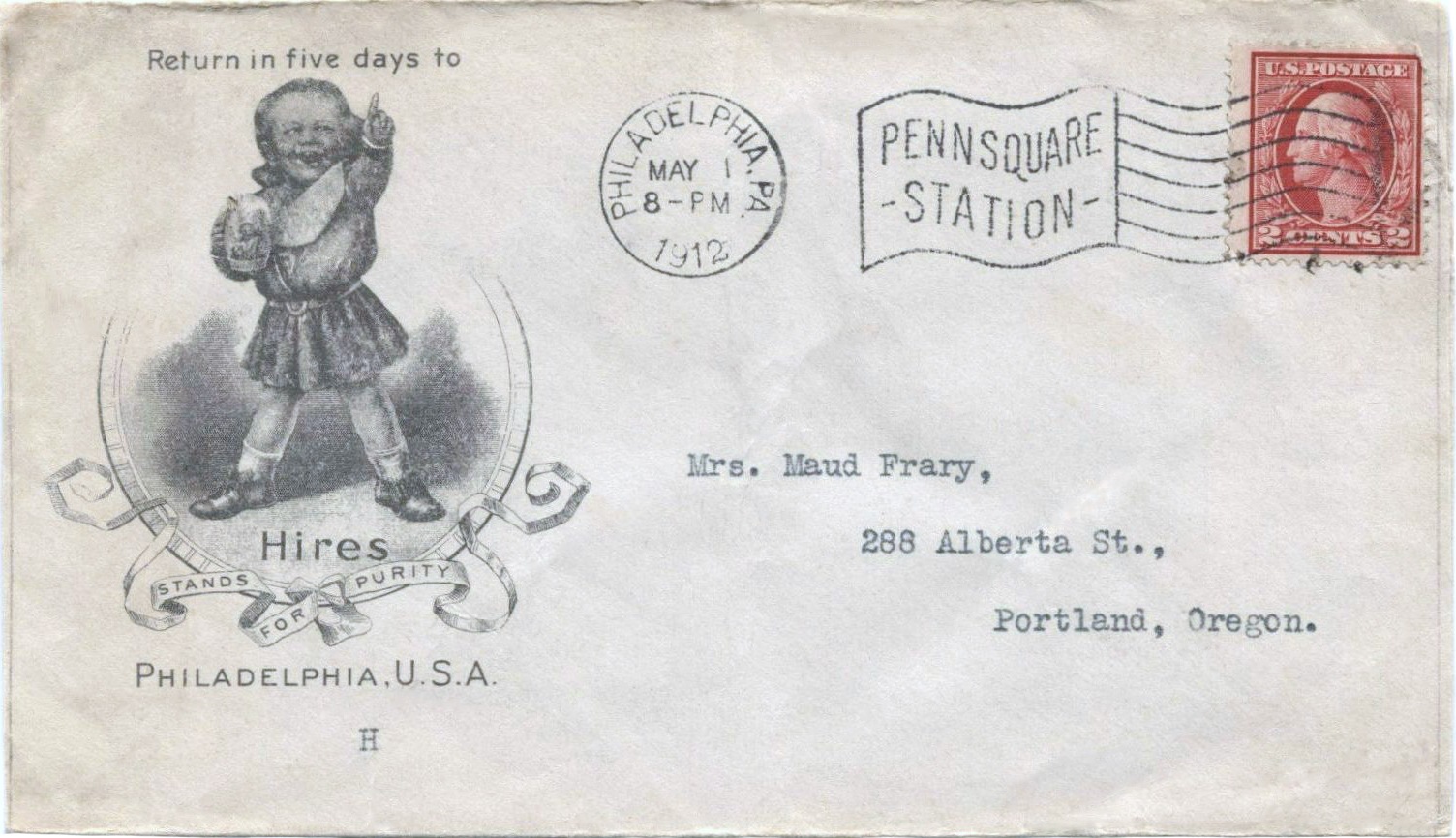

(Figure 1912-01.5, Hires

envelope postmarked May 1, 1912)

Note this advertisement’s invitation for readers to

“Write for premium puzzle.”

(Figure

1912-02, The

Youth’s Companion, May 2, 1912)

The

Hires name appeared frequently in

Printers’ Ink articles during May, 1912.

This article written by Roy W. Johnson was published in the May

16, 1912 issue and provides considerable insight into the major

challenges Charles E. Hires faced when striving to catch up with the

soft drink industry’s shift to the use of soda fountains, while also

contending with “substitution evil.”

WINNING BACK THE LOST MARKET

HOW THE CONCERN WHICH DID NOT FOLLOW

CHANGING CONDITIONS IS NOW TRYING TO OVERTAKE THEM – AN ANALYSIS OF THE

FIELD WHICH SUGGESTED A NEW PRODUCT AND OPENED UNSUSPECTED SALES

POSSIBILITIES – GETTING THE CONSUMER TO ASK FOR “HIRES” INSTEAD OF “ROOT

BEER”

Twenty-five years ago the family gathered around and

imbibed home-brewed root beer which was made with “household extract”

and yeast purchased at the grocery store.

Five gallons of the product were prepared at a time, and stored

in bottles down cellar, to be used as wanted.

Today the family foregathers at the nearest drugstore and

chooses, from a large assortment, the drinks which are prepared on the

spot in exactly the quantity desired for immediate consumption.

They pay more per drink, it is true, but there are no bottles to

open or to rinse afterwards, no thoughts of the glassware which must be

“washed up” and no danger of a discovery that the supply is exhausted.

Looking back over the of twenty-five years it is easy to see how

the market has changed from the patent beer bottle to the soda-fountain,

from the grocery to the drugstore, but it didn’t all happen in a day or

a year and it wasn’t so easy to recognize what was going on.

The Charles E. Hires Company, of Philadelphia, makers

of the original root beer extract, didn’t recognize it until some people

would have said it was everlastingly too late.

Charles E. Hires, the founder of the business, is frank in

saying: “I should have put a syrup on the market years ago.”

But it was not done, and there are plenty of reasons why it was

not done which seem perfectly reasonable.

Briefly stated, the distribution of the company for

the “household extract” was chiefly through grocery stores, and to put

out a syrup would mean the development of drugstores with a consequent

feeling on the part of the grocers that the company was competing with

them. Add to that the fact

that the soda-fountain business was regarded as more or less of a fad,

and you have the reason why a Hires Root Beer syrup was not put on the

market twenty years ago.

But the results were disastrous.

Root beers sprang up on every hand, in response to the demand for

the drink – a demand which Hires had created by the sale of the

household extract for a number of years.

These were sold simply as “root beer,” and the name of Hires

dropped out of sight except in connection with the home preparation of

the drink. Moreover other

drinks – Coca-Cola, Moxie, Grape Juice, etc. – came in with the force of

consumer advertising behind them, and took a large share of the

soda-fountain trade. The

consumer stopped calling even for “root beer,” and began to demand

drinks by their trade names.

And all the while there was less and less demand for home-brewed

refreshments, and more and more demand for the soda-fountain beverages.

The soda-fountain habit spread into the smallest towns, leaving

only the truly rural districts to make any consistent demand for

household extract with which to make their own root beer.

Out of four “business doctors” three would probably

have said that the market was gone beyond recall, and it would be better

to quit than to spend money trying to compete with the heavy advertising

of rival drinks and to try to win back trade to a forgotten brand.

In many ways it would be easier to win them over to a

new brand.

And even if they were won back, there was the

substitution evil to face.

Anybody could make a “root beer,” almost exactly similar in taste, and

make it a whole lot cheaper than Hires.

Of course, it wouldn’t be quite so wholesome, but that wouldn’t

have any effect upon the sale of it, because wholesomeness isn’t a prime

requisite to the soda-fountain patron.

Recreating a demand for “root beer” would be simply making a

market for a lot of unbranded syrups, and to create a demand for “Hires”

would mean the usual uphill fight for a brand which, in the minds of a

good many people, was a “has-been.”

But in spite of the rather gloomy outlook, Mr. Hires

determined that he would “come back,” and not only would he come back,

but he would advertise Hires.

A careful analysis of the new market developed, as a real

analysis usually does, some important facts.

In the first place, it

developed that the weakest spot in the soft drink business is the lack

of uniformity in the product unless the drink complete is poured from a

bottle. The flavor depends

upon the quantity of syrup placed in the drink, and in the hurry of

mixing by uninterested clerks the usual procedure is to supply too much

syrup. If there is too

little, the customer will not find the drink palatable, while too much

is erring on the safe side at least.

Some soft drink manufacturers have endeavored to get

around the difficulty by supplying the product ready mixed in bottles.

But the soda clerk is not partial to this system because of the

extra labor necessary to open the bottle, re-cork it and place it on the

ice. Bottled soft drinks

have been successful to a certain extent when sold by the case for home

consumption, but it was not considered wise to put out another bottled

beverage for soda fountain use.

It would not only run up against more or less opposition from the

clerks who served it, but would also run counter to the habits of

customers, who were used to seeing the whole process of mixing before

their eyes. Indeed, so

strong is the prejudice against having things done where the customer

cannot see them that practically all soda clerks are instructed to

perform every operation as openly as possible.

Breaking an egg under the counter would not be tolerated for a

moment in any good drug store.

From the standpoint of the manufacturer, the practice

of giving too much syrup per drink was not altogether a bad thing,

because it used more syrup.

But from the dealer’s standpoint it represented a loss, and the Hires

people needed the good-will of the dealers quite as much as that of

consumers. So it was

decided that some means of measuring the syrup accurately was wanted,

both to win over the dealer by increasing his profits, and to satisfy

the consumer by giving him his root beer always in the right

proportions.

MACHINE THAT WIDENED THE MARKET

The result was the Munimaker, a pocket edition of a

soda fountain. It contains

a reservoir for Hires syrup, and a coil running through an ice chamber

to which a soda tank is connected.

Pushing the controlling handle to the right automatically mixes

the Hires syrup with the carbonated water in exactly the right

proportions, and a turn to the left dispenses plain soda water.

The addition of this machine to the Hires line not

only provided the means for serving the drink easily, quickly and

accurately, but widened the market for Hires syrup enormously.

For the syrup could profitably be sold through this machine in

places where there was no soda fountain.

The machine, plus a few bottles of flavoring syrups, was a

full-fledged soda-fountain in itself.

So the company is equipping cigar stores, steamboats, railroad

stations, etc., with the means thereby they become customers of the

Charles E. Hires Company.

Not only does the machine earn a profit by selling

the syrup, but it is actually purchased at a profit from the company.

The dealer pays $150 for his Munimaker, and signs a contract to

use it only in connection with Hires syrup.

He is privileged to use it as a soda-fountain all he likes, so

long as the reservoir is filled with Hires syrup.

But it is a standing and continuous advertisement for Hires,

since that is the only name which appears on it, and it is prominently

displayed.

The dealer is persuaded to part with his money for

the machine, on the showing of the saving it will make for him.

The average number of five-cent drinks per gallon of syrup under

ordinary conditions is sixty-five, while the machine will dispense 140,

and do it with less trouble.

A certain department store which set up Munimaker booths in

several places throughout the store, reported to the Hires company that

in one day a single machine dispensed more than 1,400 drinks.

So the saving on syrup at $1.50 per gallon is not inconsiderable.

But perhaps the most striking feature of the machine

system is the new sales auxiliaries it developed.

One of the company’s salesmen sold a machine to a Y.M.C.A. to

serve drinks to its members as a means of getting a little revenue.

By and by the sales manager received a letter from the secretary

of this Y.M.C.A. branch stating that the Munimaker was earning three

dollars a day. It was not a

very big return, but looked promising enough to warrant a little

investigation of the Y.M.C.A. field.

As a result the International Committee of the Y.M.C.A. has taken

up the matter officially, and it is stated that the company is the only

concern ever invited to attend a meeting of the International Committee

in a business capacity. The

machine appeals to the Y.M.C.A. people because it earns an income, and

moreover is in line with their campaign against the liquor traffic.

Thus we find a definite section of the campaign devoted to sales

promotion among Y.M.C.A. secretaries, and they are rapidly being turned

into boosters for Hires.

Stranger still perhaps, while the Y.M.C.A. is

boosting the machine because it helps fight the liquor traffic, the

liquor traffic itself is getting interested.

A hotel keeper who had bought a machine for use in his barroom

wrote to the company that it had increased his sales of soft drinks from

two gallons of syrup per month to

eleven gallons per week, and he wanted to know if he couldn’t have

the exclusive agency for it in his territory among saloons.

He liked the machine because it earned a profit, saved opening

bottles, and tended to reduce the frequency of “drunks.”

The company is going after cigar stores, railroad

stations, steamboat lines, pool rooms, and other places where people

congregate, selling a machine and reaping the attendant harvest of syrup

sales.

So much for the dealer.

It remained to put the goods into the mouths of consumers,

literally and figuratively.

It was fairly widely known, from the household extract advertising, that

Hires made root beer. The

company desired to get all possible advantage from this knowledge of the

name, but it was highly important that the consumer should not ask for

“root beer,” because, except in places where the Munimaker was

installed, it would be extremely likely that it would not be Hires.

Of course, the Hires company sells syrup to a great many dealers

who have not purchased a machine, for serving in the ordinary way, and

it was not possible nor advisable to direct consumers to look for the

Munimaker. Such a process

would be entering into competition with the company’s own trade to a

certain extent, and could hardly be successful without a wide

distribution of the expensive machines.

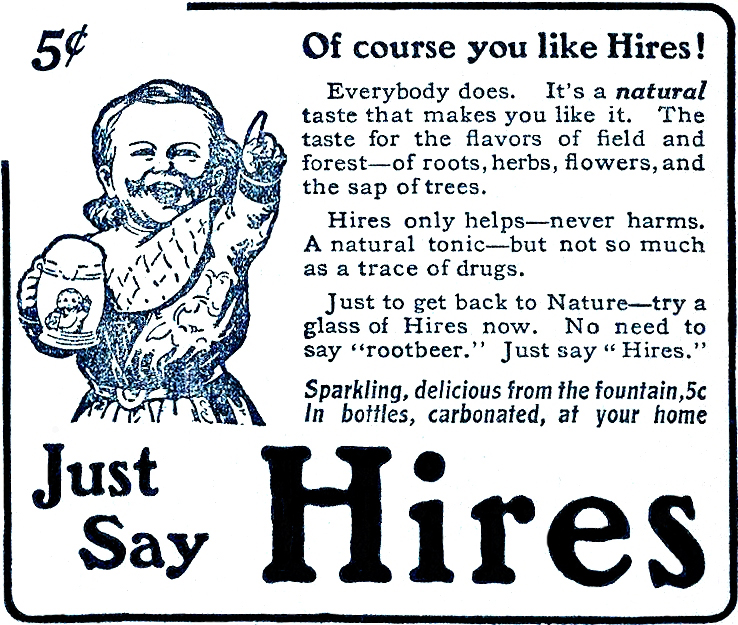

EMPHASIS ON THE BRAND

The line followed has been to gradually eliminate the

words “root beer” from all consumer advertising (except that which deals

with the household extract).

The consumer is directed to “Ask for Hires” and is told that it

is not necessary to say “root beer.”

The latest series of dealer signs put out by the company do not

include the words “root beer” at all, and previous series have gradually

subordinated it more and more to the name of the maker.

The public is told about the Munimaker in a roundabout way,

without laying any special emphasis upon it.

Once or twice a year an ad is run which features it, and the rest

of the time the drink itself is made the prominent subject of the ad.

The most striking results, of course, have come from

those places in which the Munimaker is installed, and the machines are

being sold rapidly because they are recognized as a help to the dealer.

The company has more than a thousand testimonials on file from

users of the machine, and practically all of them report increases of

from 15 to 300 percent.

These increases, of course, can mean only one thing: a corresponding

increase in the sale of Hires syrup.

I asked Mr. Hires about the

household extract, which is still being sold.

I wanted to know whether he did not think that it was a form of

competition with his soda fountain trade.

He said emphatically “No.”

It helps the business, he maintains, in so far as it has any

effect upon it, for the person who gets the root beer taste doesn’t

always want to wait until he gets home and will drop into a place where

there is a soda fountain.

And the fact that it is advertised as “root beer” while the syrup is

“Hires” tends to keep the two separate.

It is obvious, moreover, that the household extract is seldom if

ever advertised in the same mediums which carry the advertising for the

soda fountain trade, for people within easy reach of a fountain will not

take the trouble to prepare the drink at home.

This little distinction between “Hires” and “root

beer” doesn’t look very important, but it counts on the balance-sheet at

the end of the month.

The May 23, 1912 issue of

Printers’ Ink included this

related follow-up article:

A TEST OF THE VALUE OF BILLBOARDS

HOW THE CHARLES E. HIRES COMPANY TRIED

OUT POSTERS IN A CERTAIN TERRITORY – TAKING ADVANTAGE OF POPULAR

SENTIMENT – THE DANGER OF “KNOCKING”

When the Charles E. Hires Company, makers of Hires

Rootbeer, started the campaign to regain the lost market, as told in

Printers’ Ink for May 16, it

was desired to use every means would be profitable.

Some said billboards would pay – others said they would not.

The only way to find out definitely was to try and see.

So the company resolved to try the experiment, and to

make it as fair as possible, the district sales manager of the territory

where the posting was to be done was told nothing about it in advance.

Moreover the territory selected was one in which competition was

particularly keen.

It was just at the time when

the agitation over the Pure Food law was at its height, and it was

thought that some advantage should be taken of the popular interest in

the subject. So the line “A

Drink – Not a Drug” was given a prominent place in the poster, as it was

in all the magazine and newspaper advertising.

Other prominent features desired were, of course, the name Hires

and the familiar trademark.

A background of a meadow scene was added to connote the origin of the

drink from familiar roots and bark.

As has been mentioned, the posters were placed

without notice to the district sales manager.

In a few days he wrote in and wanted to know how widely they had

been distributed through his territory, but got no specific information.

A little later he wrote that “business had improved somewhat.”

By the time the posting contract expired, the company had a

letter from that sales manager stating that his business in Hires had

increased three hundred percent since the posters went up.

Mr. Hires attributes the unusual results to the fact

that public sentiment was aroused over the Pure Food agitation.

However the line “A Drink – Not A drug” might easily be construed

as a “knock” or at least an insinuation, and as such it was not

considered good advertising for continuous use.

The company is using posters again this year, as a part of the

general campaign to popularize the name “Hires” following the wider

distribution of the dispensing machine.

N.W. Ayer & Son, Hires’ long-time advertising agency,

placed a two page advertisement in the May 23, 1912 issue of

Printers’ Ink including a

billboard image Ayers produced showing “One of the 16-sheet Hires

posters just off the press.”

The sign features the Hires Boy admonishing readers to “Say Hires

to the fountain man but don��t be put off with a substitute – Get Hires!

Hires! Hires!”

The same issue of

Printers’ Ink also included this article quoting Charles E. Hires:

WHICH FIRST – POSTERS OR SALESMEN?

Views and Experiences of Leading

Advertisers in the Matter of Opening Up New Territory or Renewing Demand

in Old

Poster advertising is a sort of double-barreled

proposition, in that it appeals to both consumer and dealer about

equally. Newspaper and

magazine advertising can be “addressed” to the consumer.

It will, of course, be read by numbers of dealers, but it doesn’t

stand out in the bold fashion of talking to everybody as a poster does.

And of course trade-paper advertiser does not reach the consumer

at all.

That double-barreled quality in the poster makes it a

particularly strong medium in a campaign for getting distribution,

because the dealer not only sees it himself, but he knows that at the

same time his customers cannot help seeing it.

It is particularly strong and tangible evidence that something is

“happening” to promote the product advertised.

It is a valuable aid to the salesmen in a distribution campaign,

but just because it has an effect upon the consumer as well as the

dealer it must be used with care lest consumers be sent to ask the store

for the goods before they are in stock.

Just

when, in a distribution

campaign, it is best to post a town – if ahead of the salesmen, how far

ahead? – is a delicate question, and the opinions of national

advertisers who have used posters in this way should be

interesting…Charles E. Hires, president of the Charles E. Hires Company

(Hires Root Beer):

“We find the best results in advertising through

posters are achieved when the billposting is done almost simultaneously

with the appearance of the sales force.

“Too many promises have been made by would-be

conquerors of what they ‘will do’ or what they ‘expect to do,’ to set

the world afire, and merchants have become weary of such promises, and

skeptical as to their fulfillment.

“But have the town painted red on Monday and the

sales force enter on Wednesday, and they are sure of a hearty welcome,

provided, certainly, that they come to offer an article of proven

excellence, an article of good repute.

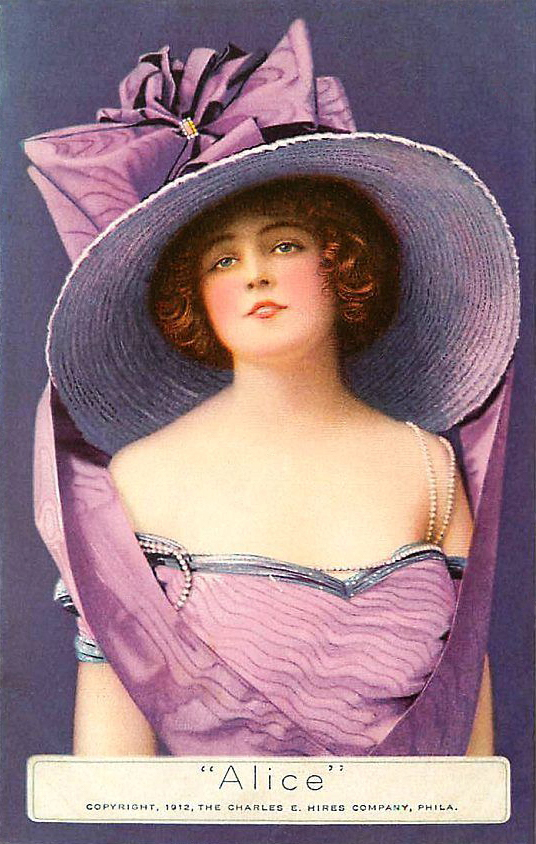

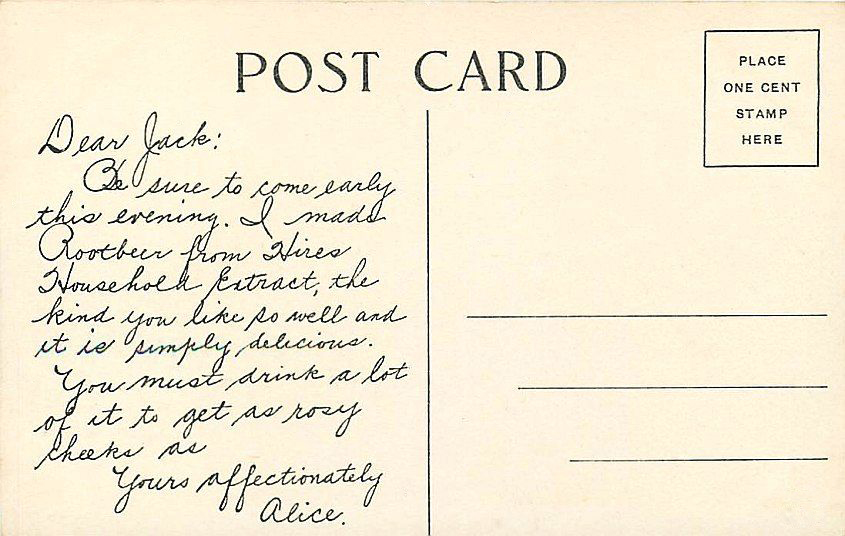

1912 brought the publication of a postcard featuring

“Alice," a beautiful young woman who was considered “The Hires Girl.”

The back includes a pre-printed message from Alice to “Jack.”

(Figure 1912-03, “Alice”

postcard, front)

(Figure 1912-03, “Alice”

postcard, back with pre-printed message)

Alice’s larger-sized image for this poster reveals the long white gloves

she wore in the original portrait.

The lower right-hand corner is marked “© 1912 THE CHARLES E.

HIRES COMPANY.”

(Figure 1912-04, “Alice”

cardboard poster, 14.0” x 11.0”)

This fancy, pressed tin sign was manufactured by Mayer and Lavenson of New York City.

(Figure 1912-05, pressed tin

sign)

Here's a similarly fancy, 14.0" x 12.5" pressed tin sign bearing no Hires item number nor maker's information. The word "Hires" is embossed.

(Figure 1912-05.2, pressed tin

sign)

(Figure 1912-05.5, newpaper

advertisement, 7.0" x 9.5")

(Figure 1912-05.8, Chicago

American newpaper, July 24, 1912)

This “Just Say Hires” series ran in the

San Francisco Chronicle, San

Francisco, California.

(Figure 1912-06,

San Francisco Chronicle)

(Figure 1912-07,

San Francisco Chronicle)

(Figure 1912-08,

San Francisco Chronicle)

(Figure 1912-09,

San Francisco Chronicle)

Charles E. Hires Company sales for 1912 were listed

as 166,066,176 glasses.

%20Rootbeer%20-%20pressed%20tin%20sign.jpg)