1921

IT HAPPENED IN…1921

World War I had created boom times for American

industry and workers, but as the wartime demand for goods ended, the

U.S. experienced an economic depression.

The Emergency Immigration Act of 1921 limited the

annual number of immigrants allowed to enter the U.S. to 357,000.

The Act favored northern Europeans, severely restricting

people from eastern and southern Europe and the Orient.

Organized labor backed the measure, as did social reformers

who felt the city slums problem wouldn’t be solved unless the tide

of incoming poor illiterates was curbed.

Prohibition fueled increased crime in the U.S.

and changed America’s social fabric.

Heart disease was the number one cause of death.

Despite being illegal in 14 states and under

review in 28 other states, annual cigarette consumption climbed to

43 billion. Iowa became

the first state to tax cigarettes.

A Ku Klux Klan revival began with lawlessness

that targeted Catholics.

1.5 million new automobiles were produced in

1921, with Ford controlling 55% of the industry.

The total number of U.S. vehicle registrations rose to 10.5

million.

Sixteen year old Margaret Gorman won the Atlantic

City, New Jersey Pageant’s Golden Mermaid trophy and was later

dubbed the first “Miss America.”

Betty Crocker was created as part of a

promotional campaign for Gold Medal Flour.

Newly introduced products and inventions included

Drano, the polygraph, leaded gasoline, Chanel No. 5 perfume, Mounds

candy bars, packaged potato chips, iodized salt, Wheaties cereal,

and Wonder Bread.

The opening of a White Castle hamburger

restaurant in Wichita, Kansas marked the founding of the world’s

first fast food chain.

The 10% federal excise tax on soft drinks was

changed to a tax on syrup and carbonic gas.

The NuGrape Company of America was organized in

Atlanta, Georgia.

6,038 U.S. soft drink bottling plants were in

operation. Per capita

consumption was 42.1 bottles.

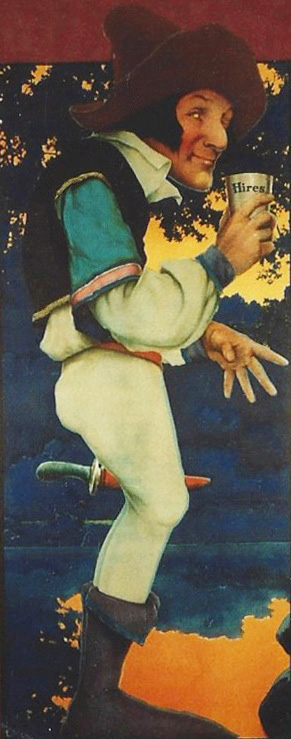

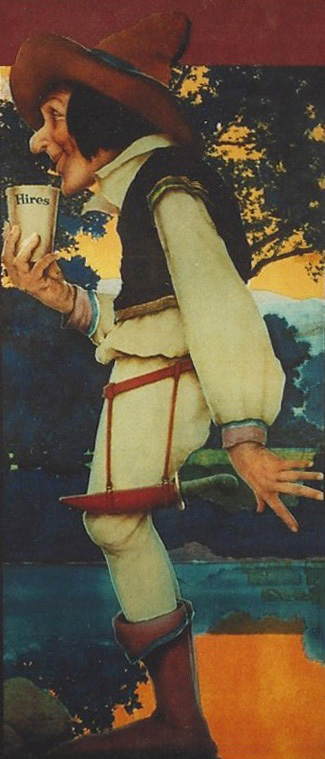

Early in 1921 Hires commissioned famed American painter Maxfield Parrish to create illustrations for use with Hires advertisements. These two original Parrish paintings of gnomes are framed and in the possession of the Hires family.

(Figure 1921-01, gnome

paintings by Maxfield Parrish, Hires Family Archives)

This advertisement includes the Maxfield Parrish drawn gnome looking to

the left. Note the

reference to “the Hires standard for 50 years,” suggesting the company

was founded in 1871.

And once again

mention of "the high cost of the best ingredients." The

identical advertisement was also placed in the July, 1921 issue of

The Century Magazine.

(Figure 1921-02,

Review of Reviews)

(Figure 1921-02.5, Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, April 18, 1921)

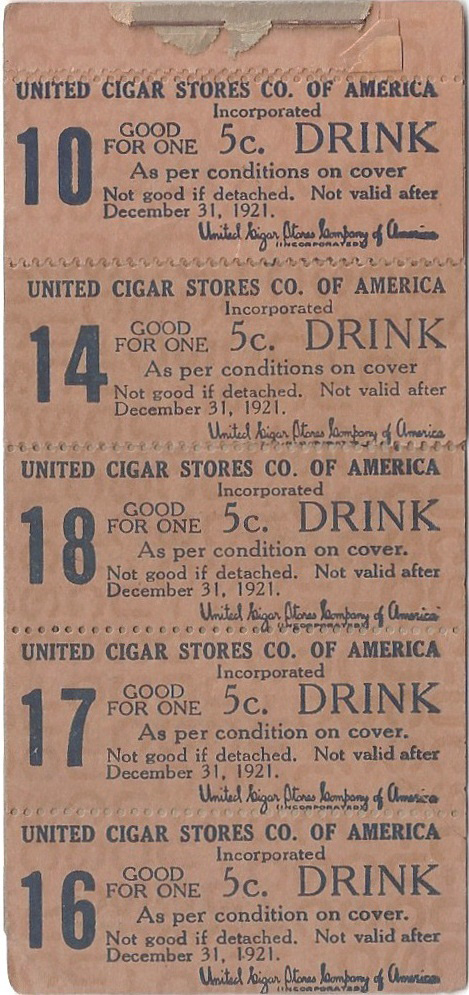

This booklet of free drink coupons was produced in conjunction with United Cigar Stores Company of America. These coupons expired December 31, 1921.

(Figure 1921-03, free drink

coupons, front cover missing, 5.0” x 2.25”)

(Figure 1921-03, free drink

coupons, back cover)

The following article by Roy W. Johnson, “The Story of Hires,” appeared in the April, 1921 issue of Printers’ Ink Monthly, and was subsequently reprinted in The American Bottler magazine in May, 1921. The article is presented here in its entirety. Selected excerpts have been cited in other chapters based on references to specific years, time periods, events, and developments. The article quoted Charles E. Hires extensively and given that he personally experienced these events, his recollections are the best primary source material available.

The Story of Hires by

Roy W. Johnson

The story of Hires’ Root Beer, a product known to

three generations of consumers and one which has survived the market

changes of close to half a century, really begins with a spade full of

earth thrown out of an excavation at the corner of Ninth and Spruce

Streets, Philadelphia.

Three blocks away, at the corner of Sixth Street, a small drug store had

recently been opened, and the youthful proprietor, Mr. Charles E. Hires,

happened to be passing the spot where the excavation was in progress.

That was in 1869.

Mr. Hires has grown gray with the passing years, and is the active head

of large enterprises, including a Cuban sugar plantation of 15,000 acres

besides the root-beer business whose gross sales are in excess of

$5,000,000 a year, but he laughs with the zest of youth over the

remembrance of that shovelful of common Philadelphia dirt.

“It just goes to show,” he told me, “how opportunity

is sometimes cast at your feet, and all you need is the ability, or the

good fortune, to recognize it.

I was just starting in the retail drug business with a total

capital of $400, which had to stretch far enough to cover both fixtures

and stock. The latter, as

you may imagine, was not very extensive, but I knew fullers’ earth when

I saw it – even when it was thrown out of a hole in the ground.

Fullers’ earth was widely used in those days to take the oil out

of wool, among other things, and every wholesale and retail druggist

handled it. A good deal of

a nuisance it was, too, having to be stored in a drawer and weighed out

five cents’ worth at a time, as a rule.

But when a shovelful of it was thrown at my feet I began to see

the glimmer of an opportunity.

“I hunted up the contractor, who told me that the

dirt was being hauled a mile or so away to be dumped, and he readily

consented to separate the gray fullers’ earth from the rest and dump it

only three blocks away. I

hired an Ethiopian roustabout with a wheelbarrow, and in a week’s time I

had a ton or so of practically pure fullers’ earth piled up in the yard

behind my store ready for use.

“At that time I was rooming in a house kept by a

maiden lady, and I had noticed a number of iron rings which used to rest

her hot flatirons upon.

After considerable persuasion she loaned me one of them.

I took it to the store, filled it with fullers’ earth, pressed it

down solid, smoothed it off, and made a convenient disk of the material

which would take up less space than the loose fullers’ earth, and do

away with the muss which always accompanied its handling.

I went to a friend of mine who ran a metal-working shop, and got

some die-cut letters which would stamp the words ‘HIRES’ REFINED

FULLERS’ EARTH’ on the surface of my disks.

I procured an empty barrel, and figured out that it would hold

ten gross of the disks, suitably packed to prevent breakage.

Then I called on the biggest wholesale drug house in town, showed

my goods, and told them that I would be glad to accept payment in trade.

You will remember than my stock was pretty slender, and I was

glad to pay for more in this way.

“I sold ten barrels to my first customer, and another

concern took twenty to get a slight discount.

Within a few days I had three colored men at work in the yard,

and the maiden lady’s ironing rings were all in requisition.

I kept on taking my pay in trade, and before other people got

onto the game I had my store pretty well stocked.

Of course it wasn’t very long before contractors stopped giving

away fullers’ earth to every Tom, Dick or Harry who came along, but not

until it had served my purpose very nicely.

It was my first experience with a side line, and I have found

side lines more or less interesting ever since.

Indeed, by way of parenthesis,

it may be remarked that side lines have played a rather impressive part

of Mr. Hires’ business history, and his ability to recognize an

opportunity and develop it is his most striking characteristic.

I have already mentioned his Cuban sugar plantation, which

includes, by the way, a well equipped refinery and a railroad of its

own. He recently sold a

condensed milk business which comprised no less than twenty-six plants

and was doing a business of a million and a half per month.

For years he successfully manufactured and sold flavoring

extracts, and was a large importer of vanilla beans and crude drugs.

The root beer itself, by which his name is chiefly known to the

consuming public, was a side line which grew with the help of

advertising to a point where it occupied the main tent.

As Mr. Hires says, it was just another of the opportunities which

are lying around waiting to be discovered.

“It was some years after the

fullers’ earth episode,” he said.

“I had a man in the store, and spent most of my time selling

flavoring extracts which I had developed into a fairly substantial

business. My wife and I

were staying at a farmhouse in Morristown, N.J. and were served with a

very pleasant, sparkling drink which the housewife had made by gathering

herbs, boiling them with sugar, and bottling with yeast.

It was highly agreeable to the taste, but indulgence in it was

apt to produce a laxative effect which was not so pleasant.

I thought I saw a chance to put a similar product on the market

if that fault could be corrected, and I suppose I experimented for two

years, off and on, in the effort to produce a pure herb drink which

would be entirely neutral in its effects.

After making almost innumerable changes and additions I arrived

at a formula which has stood the test of time pretty well, as it remains

unchanged today.

"The package of dry herbs (as it was then) from which the housewife could brew her own root beer sold pretty well over the counter of my Spruce Street store, and gradually it was introduced to the trade in and around Philadelphia. I did the selling work myself, because I still had no money to spare for salesmen. Finally I found two young men who were willing to tackle the proposition on the chance of making enough cash sales to pay their traveling expenses, and they were the first salesmen I ever hired. They traveled thru the South and clear up into the Northwest on this rather precarious basis, getting enough cash from dealers in a town to carry them to the next stop. Sometimes they came pretty close to being stranded, but they made the round trip to Philadelphia all right, and many trips after that.

“Later on, of course, I put the product up in form of

a fluid extract, which, in spite of the enormous soda-fountain trade, is

still widely sold today.

And curiously enough, we are still selling the old dry-herb packages to

the Scandinavian trade of the Northwest.

‘Home Brew,’ you will observe, does not always deserve a sinister

significance.

“One morning in 1877, on my way to the store, George

W. Childs, the editor and proprietor of the

Public Ledger sat down beside

me in the Market Street cable car.

“’Mr. Hires,’ he said to me, ‘why don’t you advertise

that root beer of yours?’

“’How can I, without any money?’ I asked him.

“’Advertise to get money,’ he replied.

‘It certainly will pay you, for you have a good article.

You come around to the

Ledger office, and I’ll tell the bookkeeper not to send you any

bills until you ask for them.’

“I thought it over for a few days, and finally

accepted the offer. A young

man in the Ledger office

prepared the copy, and the advertising ran every day in one-inch

single-column space.

“Sales increased slowly at first, and then more

rapidly, until I felt justified in asking the

Ledger for a bill.

It amounted to more than $700!

I nearly had heart failure, for while I knew that advertising

cost money, I had no idea that it cost

that much.

That was really the turning point of my career as an advertiser,

for I found courage enough to let the advertising go on running while I

was paying off the $700.

For the next ten years I put every penny of profit from the

root-beer business back into advertising.

I was the first advertiser for whom Mr. Childs consented to break

the columns of the Ledger in

order to run a big type head all the way across the page.

By and by I made a contract for five lines in quite a sizable

list of newspapers, and a little later asked several advertising agents

to give me estimates on one-inch spaces in these newspapers and certain

magazines in addition. I

have since then O.K.’d appropriations for $200,000 a year with less

anxious consideration than I accorded that estimate covering my first

venture in advertising on a national scale.

Of course it is obvious that there have been many

changes and new developments in the forty-odd years during which this

product has been on the market.

Comparatively few products have come down to use from that early

period, and most of them that have done so are in the class of staple

necessities. That a

specialty so clearly in the luxury class as root beer has done so is no

small tribute to the merchandising ability of its proprietor.

For just at the time when Hires’ Root Beer had attained its

majority, so to speak, a new factor appeared on the scene which required

an entire change of base so far as merchandising and distribution were

concerned. That factor was

the soda fountain, primarily an adjunct of the drug trade, while the

distribution of Hires’ Root Beer (the household extract) was almost

exclusively confined to the grocery trade.

“Of course the soda fountain had been in use for some

years,” said Mr. Hires, “and druggists used to buy the household extract

for the purpose of making their own root beer syrup.

There was a good deal of substitution going on all the time, and

the customer who asked for root beer at a soda fountain might get

‘Hires’, but was quite likely to get some concoction put up by the

druggist himself or by some wholesale drug house.

That was not very serious, because the soda-fountain trade did

not amount to much anyway.

Then came the tremendous advertising campaigns for Coca-Cola and other

ready-prepared syrups, which began to bring the soda-fountain trade into

its own. From a negligible

factor the fountain became a very serious competitor.

The home brewing of root beer was driven farther and farther back

into the strictly rural districts, and more and more people lined up in

front of the marble and onyx counters to drink – something else.

“But when I suggested putting out a fountain syrup, I

came into conflict with my own sales force.

Their customers were the wholesale grocers, and to put out a

fountain syrup would be competing with our own trade, they said.

On this account I hesitated, much longer than I should have done

perhaps, and it was not until the season of 1905 that we put out any

Hires’ syrup at all. By

that time it looked to a good many observers as if the market had gotten

away from us indeed, and I was told more than once that it was a

hopeless job to get distribution in a new field which already was

plentifully supplied with ‘root beers’ of one kind or another.

Advertising could not help me, some people said, because while it

might be possible to persuade people to ask for ‘Hires’ Root Beer’ at

the fountain, there was no possible way to prevent them from accepting

any substitute root beer that came handy.

“That these prognostications were unfounded is fairly

evident, I think, from the fact that our sales of Hires’ Root Beer for

1920 were in excess of $5,000,000, and by far the greater part of it

consisted of fountain syrup.

The story of the method adopted has already been told in

Printers’ Ink.

It consisted, briefly, of an advertising campaign to induce the

consuming public to ask for ‘Hires’ instead of ‘root beer,’ and a

selling campaign based upon an automatic dispensing machine (a miniature

soda fountain, in fact) which we called the Munimaker.

These dispensing machines were sold to the trade at a price which

yielded us a small profit, and were so designed that they could be

placed on the soda counter, or wherever was most convenient.

They were constructed to mix automatically the proper quantity of

Hires’ syrup with carbonated water in a single operation, or they could

be used to supply carbonated water along, at the dealer’s will.

"Several thousand of these

machines were sold, first and last, not merely to regular soda-water

dispensers, but to Y.M.C.A.’s, cigar stores, poolrooms, railroad

stations, and even, in those unregenerate days, to saloons.

The dealer who purchased the machine signed a contract to fill

the reservoir with genuine Hires’ syrup, and was privileged to use it as

a soda fountain all he liked as long as he lived up to his contract.

It was not difficult to persuade dealers to pay for the machine,

because it could be demonstrated quite easily that it would soon pay for

itself in the syrup that it saved, on account of its automatic action.

The average number of drinks per gallon of syrup under ordinary

conditions was 65, while the machine proved 10, easy thoroughly mixed

and absolutely right as regards flavor.

“In our advertising we eliminated the words ‘root

beer’ entirely, and also in our counter signs, hangers, etc., and on the

strength of the demand created, backed by contracts with the retailers

who had bought machines, we stocked the wholesalers without difficulty,

frequently selling Hires’ syrup in carload lots.

On the occasion of

Printers’ Ink’s twenty-fifth

anniversary, in July, 1913, Mr. Hires wrote: “In the course of forty-odd

years I have tried many experiments, some of which have failed and many

of which have succeeded.

Sometimes I like to think that my experiments have made the advertising

business plainer to a good many other people, and since in the meantime

I have been moderately successful, I suppose that I have not advertised

altogether in vain.”

Readers of the foregoing sketch will, I think, be

quite willing to agree with him.

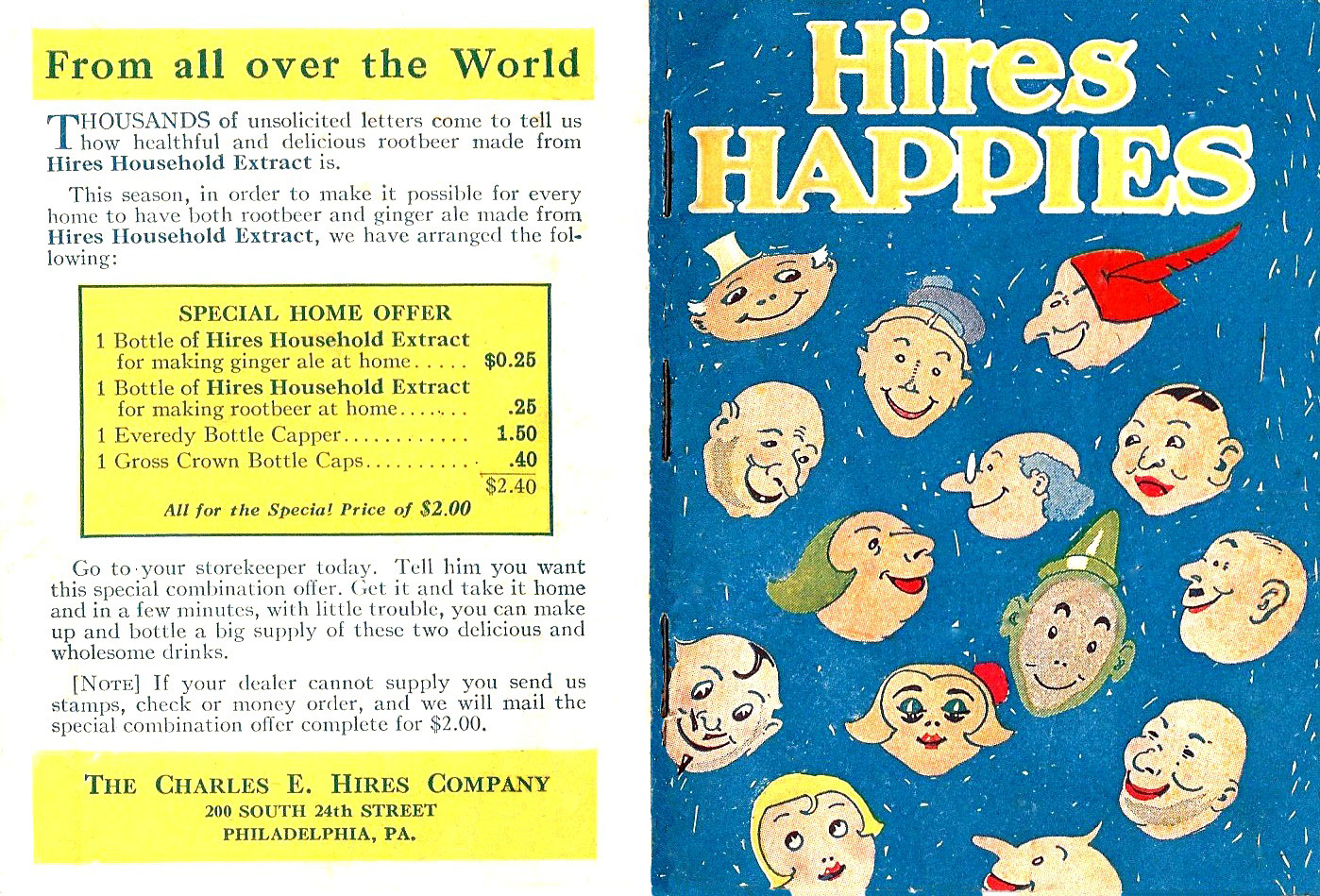

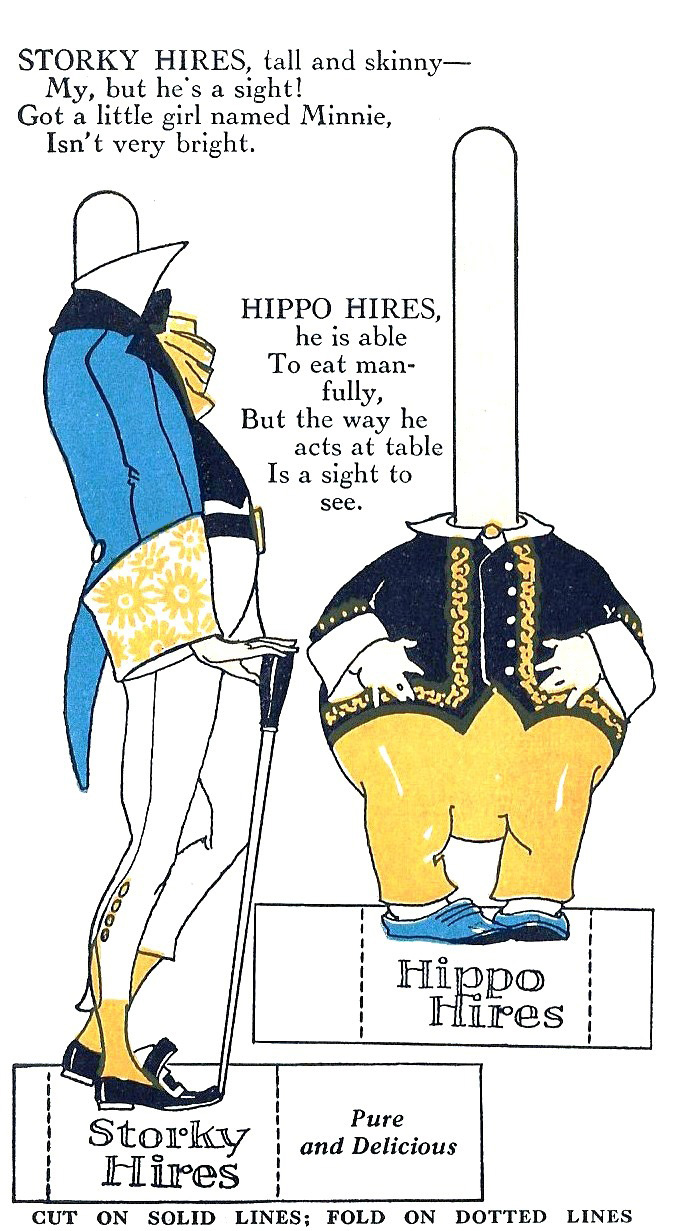

A 16 page Hires Happies booklet was designed to amuse children and promote a special offer. Hires was proclaimed “the drink that has been famous throughout America for over half a century,” yet another copywriter exaggeration attempting to push Hires Root Beer's introduction to 1871 or earlier.

(Figure

1921-04, Hires

Happies booklet, 16 pages)

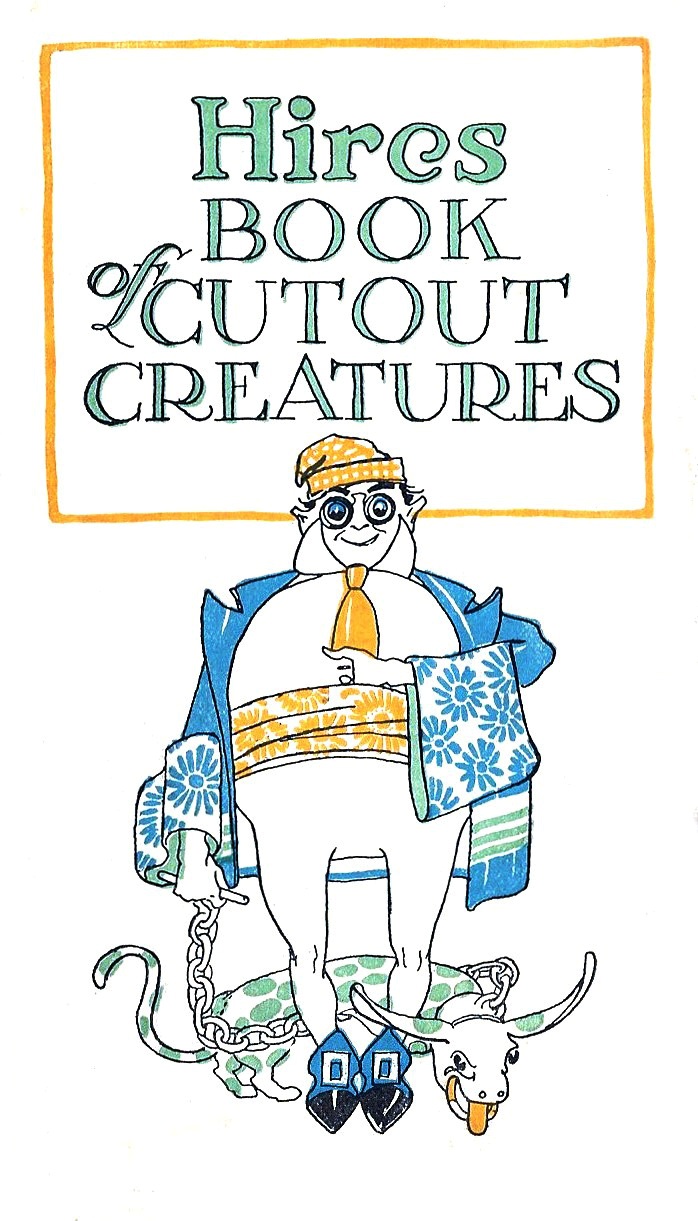

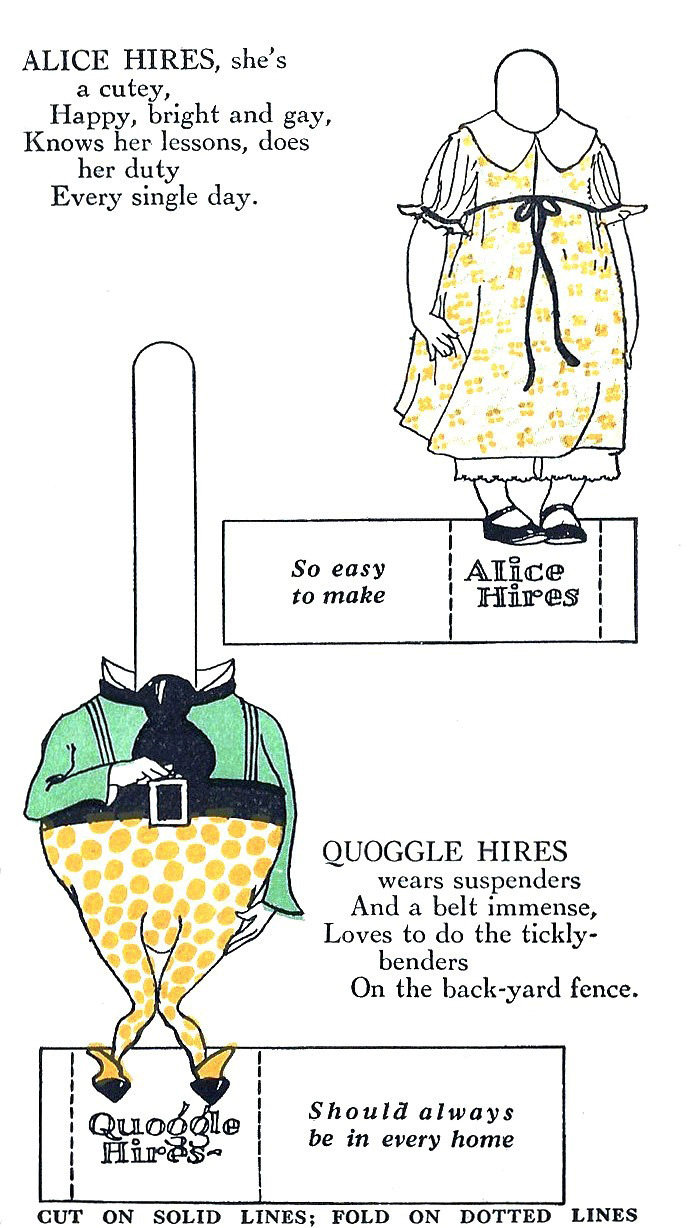

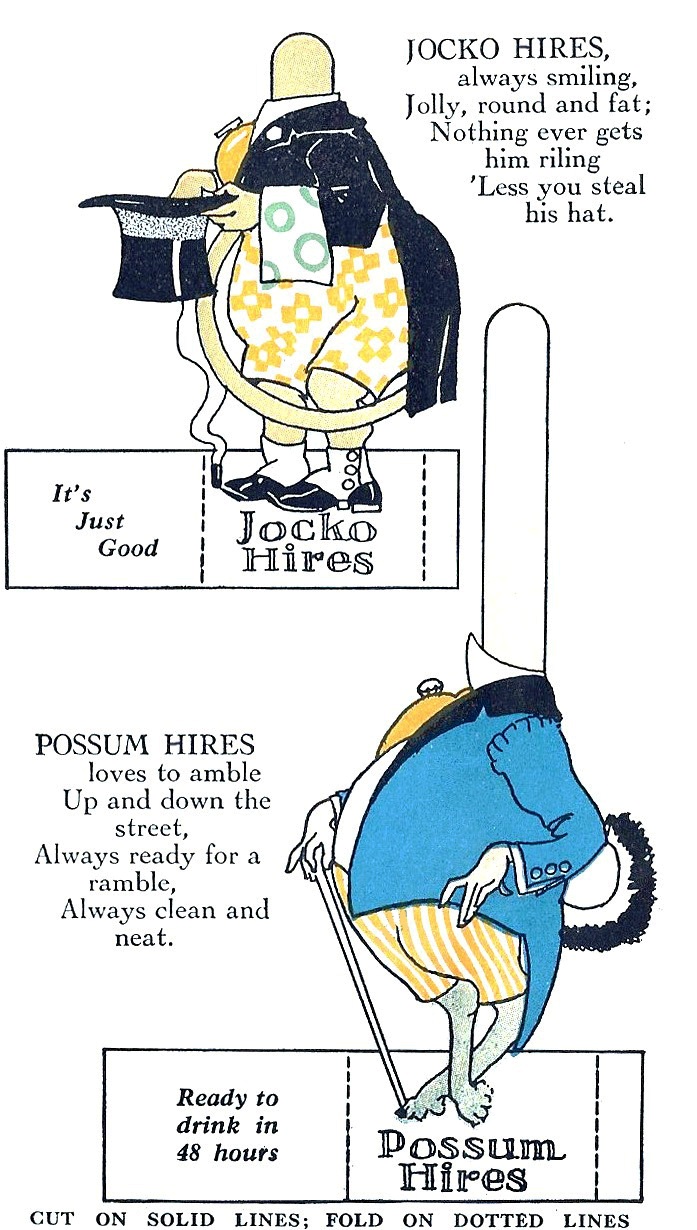

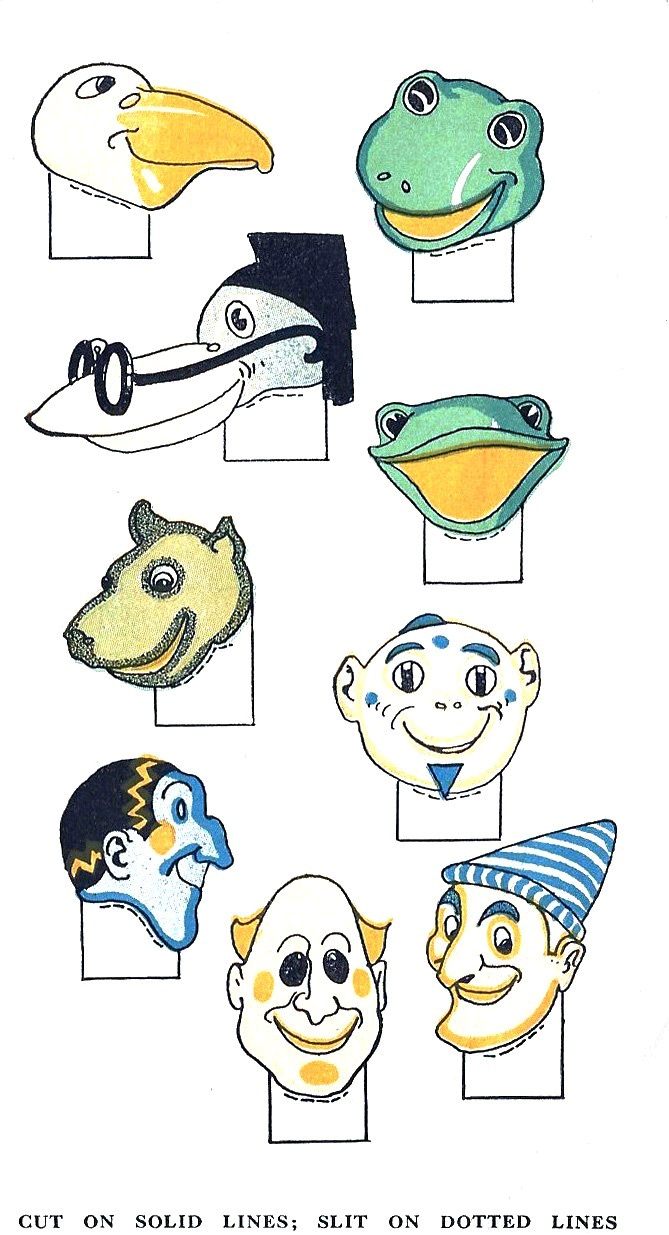

“Alice,” a veteran of previous Hires publications, made a return appearance to star in a 12 page Hires Book of Cutout Creatures booklet. Children could cut out the bodies and heads (“Ask mother to let you have a pair of scissors”) and match them in multiple ways.

(Figure

1921-05, Hires

Book of Cutout Creatures, 12 pages)

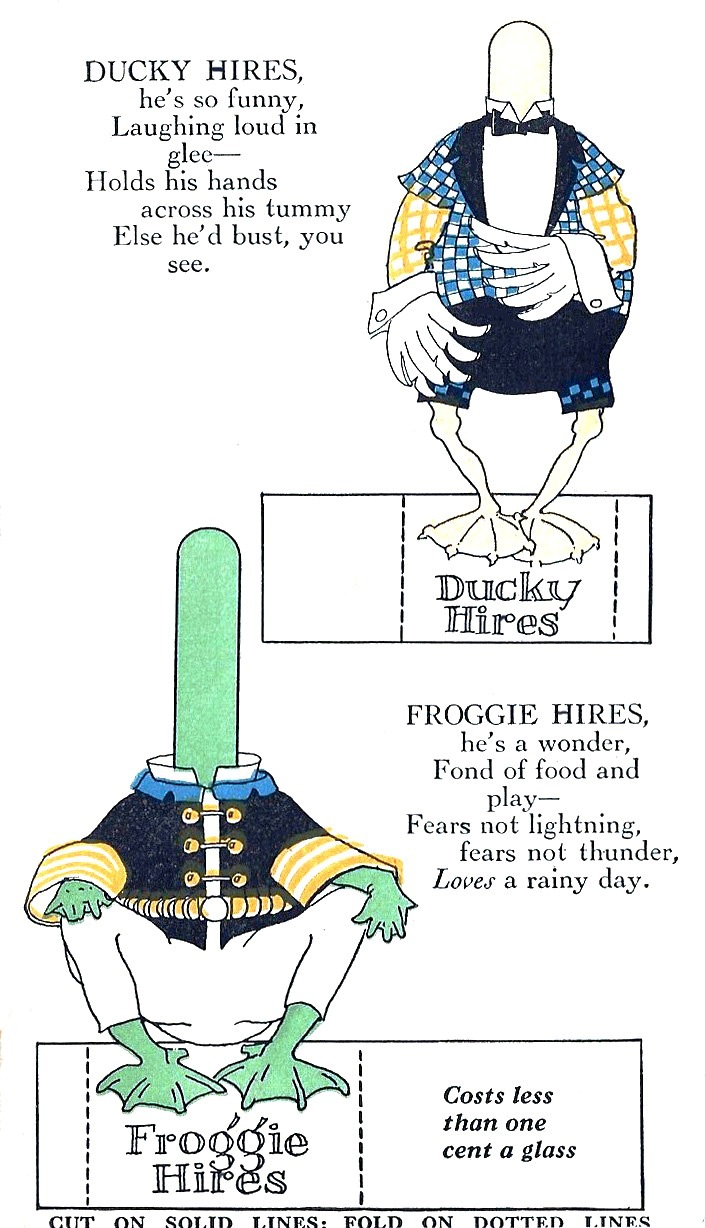

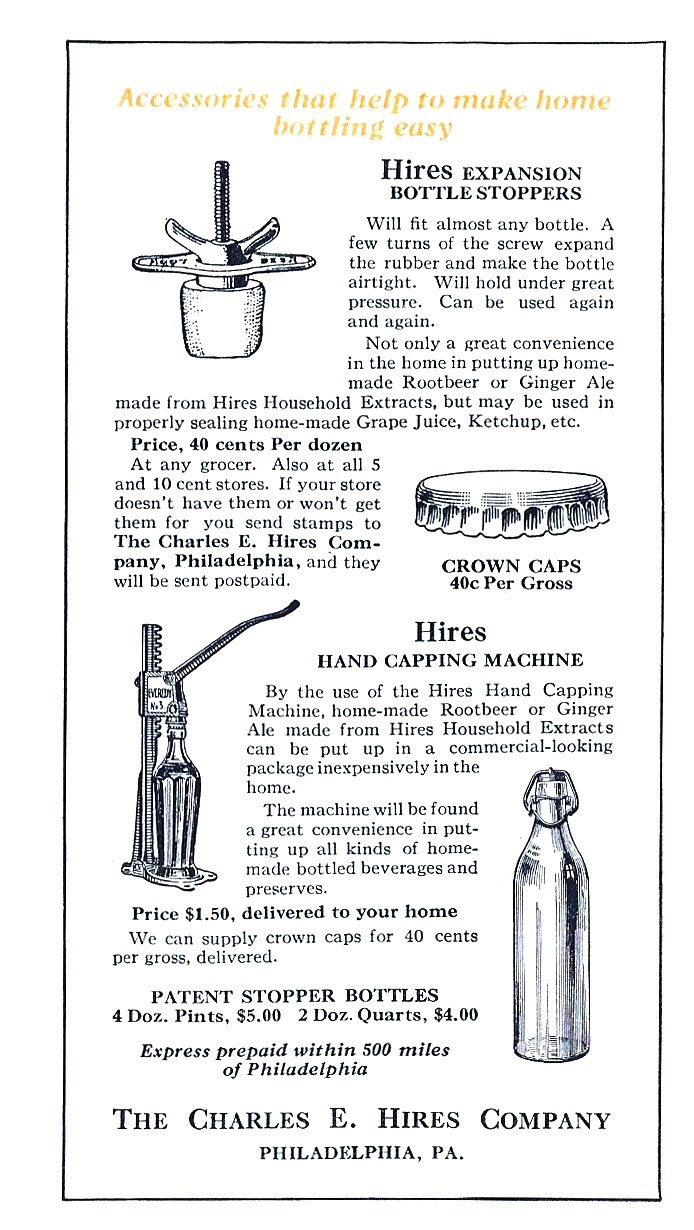

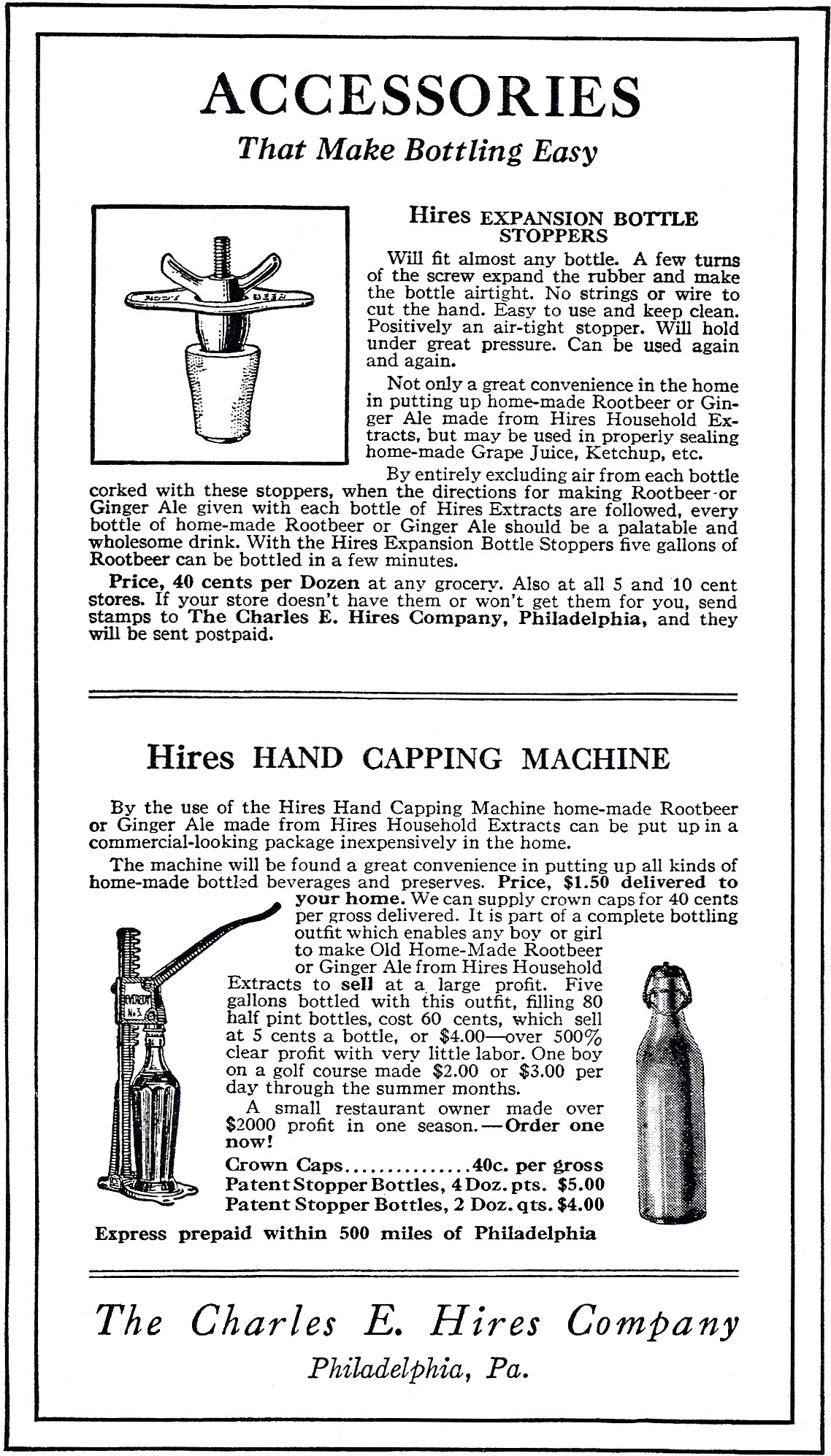

This magazine advertisement provided additional

details not included by the “Accessories that help make home bottling

easy” page in the Hires Book of

Cut-out Creatures booklet.

(Figure 1921-06, magazine

advertisement)

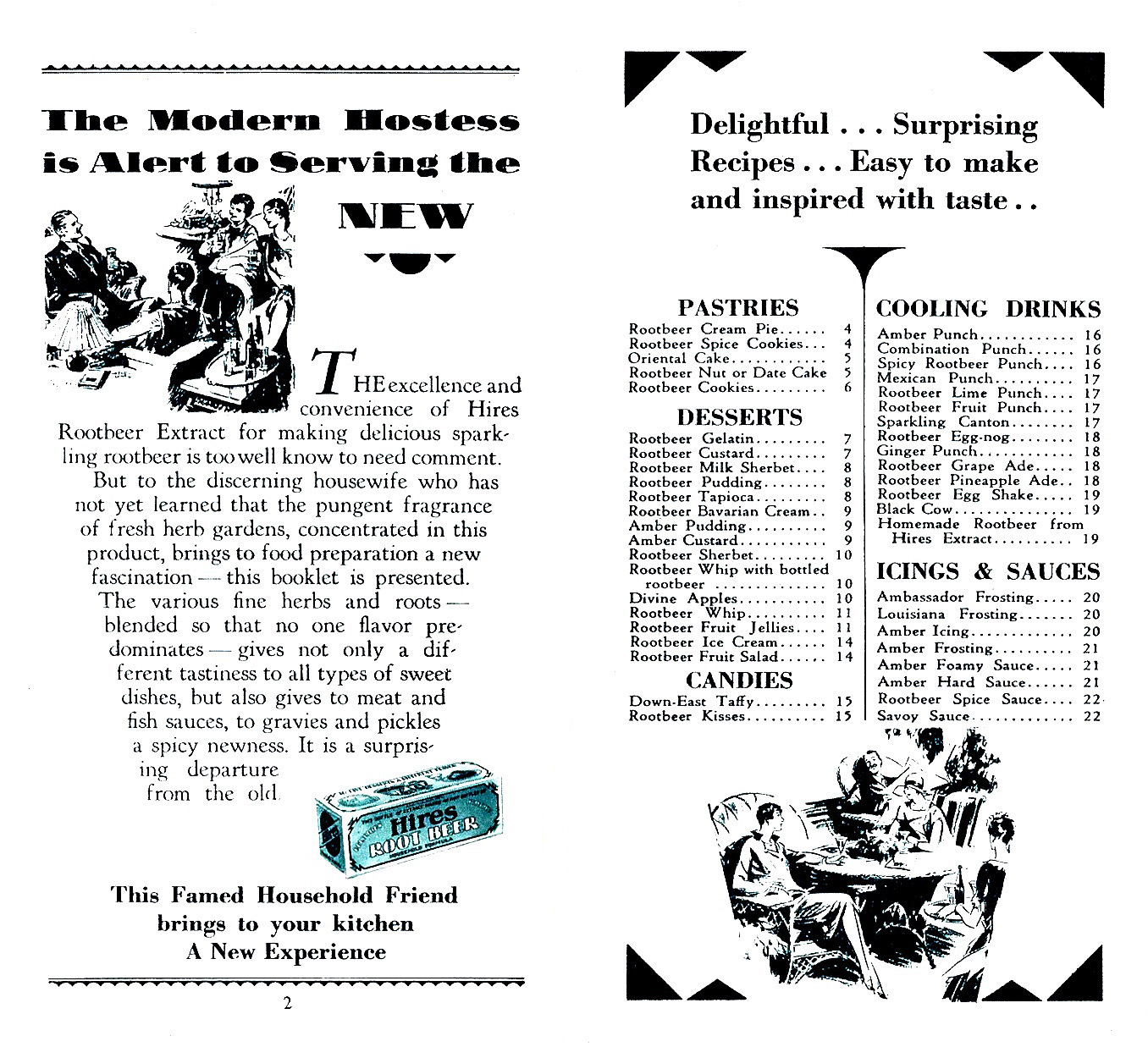

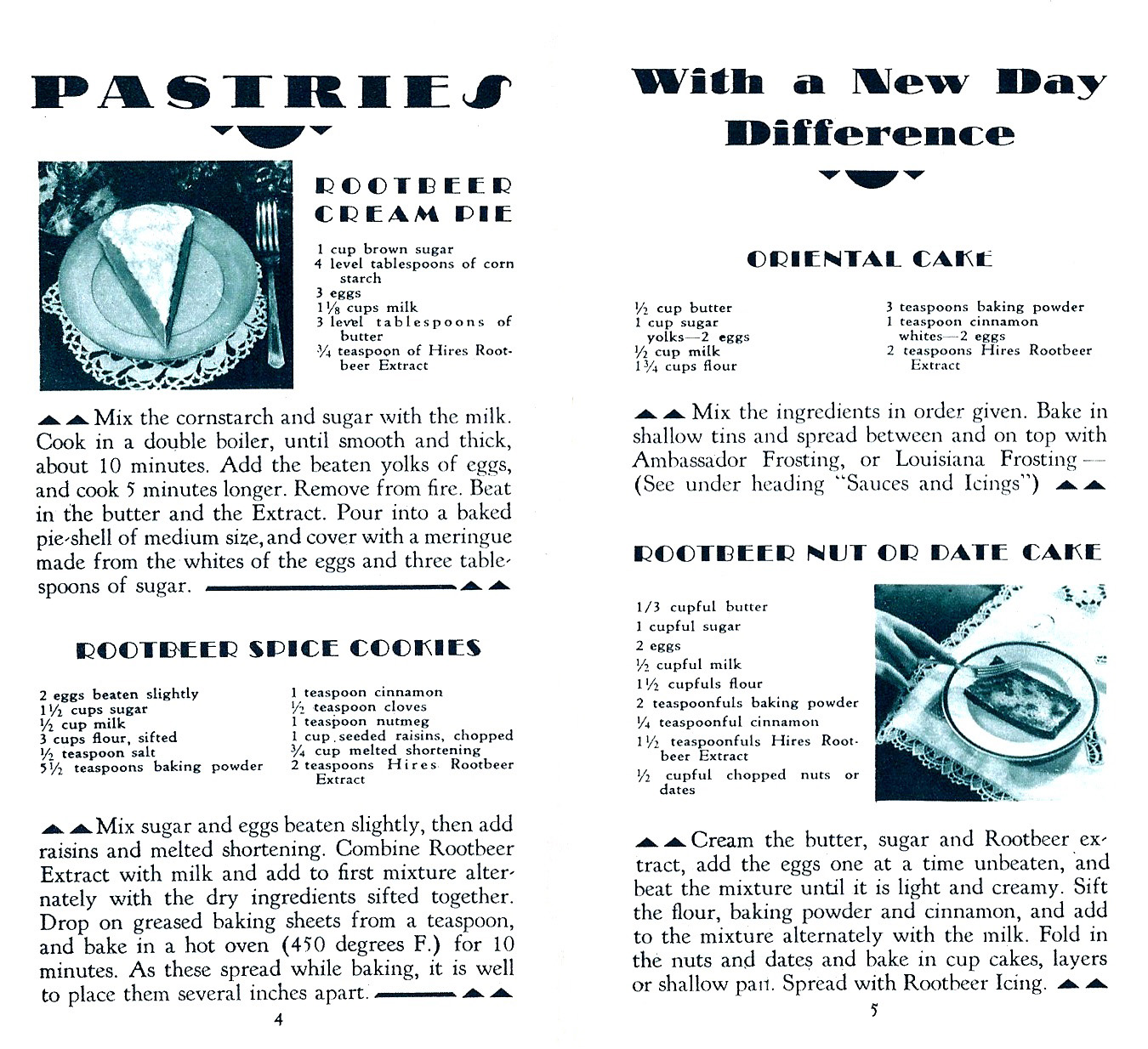

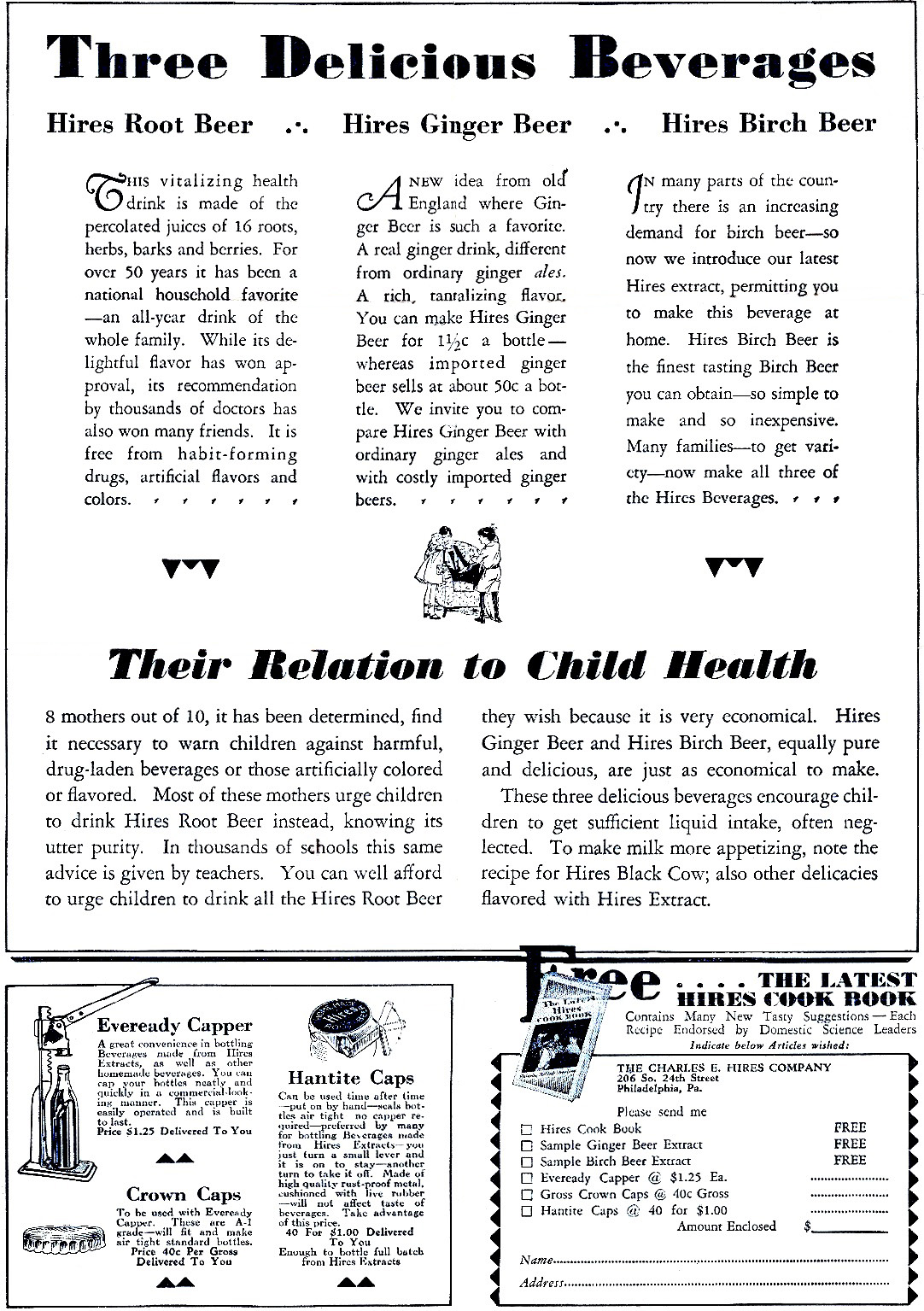

The Latest Hires Cook

Book, a 24

page booklet, stated Hires Root Beer has been “A Product of Purity Since

1869” and “For 52 years its enticing flavor has been a favorite,” claims

that seriously stretched the truth.

Note also the inside back cover refers to “A 30¢ bottle of Hires

Rootbeer Extract,” a major change marking the first price increase from

the 25¢ price of Hires Extract since its introduction.

(Figure

1921-07, The

Latest Hires Cook Book, 6.25” x 3.50”, 24 pages)

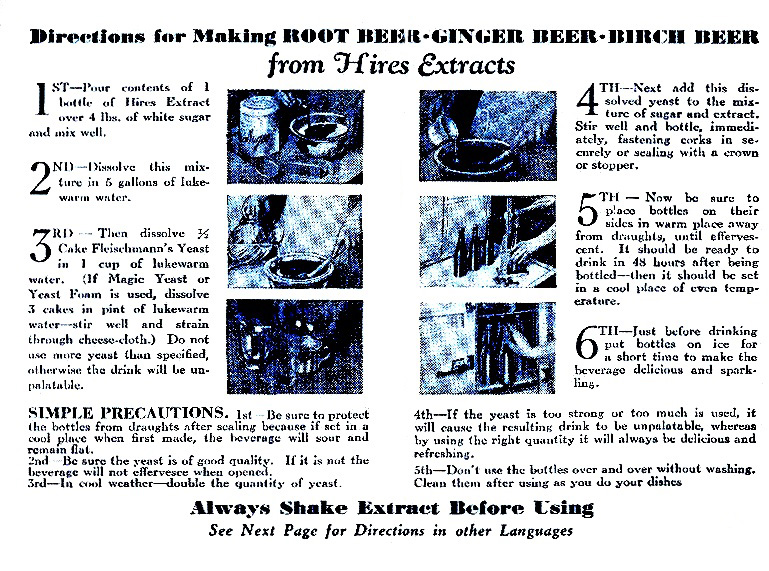

Hires Extracts cartons included directions for making Root Beer, Ginger

Beer, and Birch Beer from Hires Extracts printed in English, French,

Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Slovak, Polish, and Hebrew.

(Figure 1921-08, Hires

Extracts carton insert, back and front covers)

(Figure 1921-08, Hires

Extracts carton insert, English directions)

(Figure 1921-08, Hires

Extracts carton insert, back of unfolded insert)

This article appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer Thursday October 27, 1921:

$4500 JEWEL HAUL MADE BY BURGLAR

Home of Mrs. Charles E. Hires Robbed While Family Is at Dinner

Intruder Used Ladder, Locked Doors of Rooms and Selected Loot

Jewels valued at $4500 and $150 in cash were stolen from the bedroom of Mrs. Charles E. Hires, wife of the root beer manufacturer, while the family were dining on the first floor of their home, "Buck Lane," near Haverford Tuesday evening.

The thief, evidently a skilled "second story man," is believed to have entered the house by means of a collapsible ladder, and was seen by a domestic approaching the Hires house to visit a maid there shortly before the robbery was discovered. He carried under his arm several sections of wood, about six feet in length, which are thought to have been the ladder, and he hung his head as he went by the girl, in order to shield his face. As soon as he had passed he broke into a run, making for a small runabout halted on the street at that point, with a second man at the wheel, leaped into the machine and made off.

Jewels Taken by Thief

The stolen jewelry was listed by Mr. and Mrs. Hires as follows:

Breastpin with large diamond surrounded by two circles of smaller diamonds; platinum ring set with diamond and sapphire; breastpin with tourmalines and sapphires; diamond cluster set in platinum; circlet of 30 pearls; crescent of pearls; bar pin of platinum with topazes and pearls; plain gold wedding ring with initials, "S. E. H. to E. W., December 28, 1911 (sic)," gold link chain; round breastpin with pearls and coral; horseshoe pin with coral setting; and diamond lavalliere with three pendant stones, one of one-half karat, one of three-fourths and one of one karat.

According to the police, the thief climbed to the porch along the side of the house, entered Mrs. Hires' bedroom through a window and proceeded to lock the door leading into the hall and another one opening into Mr. Hires' room. During dinner Mr. Hires, he said, he went upstairs and it is his belief that his footsteps frightened off the intruder before he had finished his work, as a valuable diamond wrist watch and about $30 in cash, which were in one of the bureau drawers, had been overlooked.

"We had dinner at about 6:30 o'clock," Mr. Hires said yesterday, in telling of the robbery, "and after dinner Mrs. Hires and I went into the library.

"About 8 o'clock we went upstairs and we were surprised to find the two doors of my wife's room locked. To enter the room I climbed out a window to the roof and then got into the room

"Turning on the lights, I was startled to see that drawers of a bureau were pulled open, and the contents topsy turvy. One drawer had been placed on the floor.

"A maid also informed us that while we were at dinner," added Mr. Hires, "she went to arrange the beds in our rooms and found the doors of Mrs. Hires' room locked. She did not tell us about this, but advanced the information after I discovered the loss. She said she turned the knob and this may also have alarmed the thief into flight.

"The money taken was in my wife's handbag, which lay on the top of the bureau. Just before we went to dinner I had given my wife $100 in small bills and she had $50 of her own in the bag."

(Note: the description of the wedding ring engraving is an error. Charles E. Hires and Emma Waln were married December 29, 1911.)